The following is another guest post from Ed Meyertholen. I have written of the placebo effect a few times in my articles, but Ed has done a fine job of explaining how it happens and why it is important for researchers to be able to isolate it from their trials. This article was also included in the fall KDA xPress newsletter.

Even though it is a little long for a blog post, I could not find a good place to break it into two parts.

What is the Placebo Effect?

One of the difficult things in setting up any clinical trial for KD is determining what factors should be measured to assess the effectiveness of the treatment. This seems like a no-brainer – but to a researcher it is critical to the success of the study.

For those of you who were in the dutasteride clinical trial, you surely remember that different types of measurements were employed to assess the progression of the disease. The researchers were not sure what measurements were best and so hedged their bets by employing a myriad of different functional tests. Most of the tests dealt with objective measurements of muscle function (strength, for example, or how far one could walk in 2 minutes), but they also used some subjective tests, tests that tried to measure the quality of life. These latter tests were essentially questionnaires surveying how the patients felt about their physical condition and how well they felt they coped with the problems of KD.

An Actual Example

Dr. Gen Sobue’s research group just published a paper in which the compared two groups of patients with Kennedy’s Disease. This was not a report from a new clinical trial and it really offers no new insights on how to treat KD. Despite this apparent lack of relevance, I found the paper to be quite compelling. The data reported compared the rate of progression of KD in two groups of individuals, a group of men with KD that served as a placebo control in Dr. Sobue’s previous study of the effect of leuprorelin on the progression of KD (we will label these PG) and a second group of men with KD who were not part of any clinical trial, we will label them NTG.

So that it is clear, the PG group took a pill that had no therapeutic value for KD – simply, it was a sugar pill. However, they thought it was leuprorelin, a substance they were told would reduce the progression of their symptoms of KD. Since neither of these two groups received any real medicine, we would expect these two groups to show a similar disease progression over the time period of the study, 48 weeks. We will see that this is not exactly what happened.

In Dr. Sobue’s paper that served as the catalyst for this article, the

progression of the patients’ KD symptoms was also measured by both objective and subjective tests. Specifically, they compared how certain clinical ‘outcomes’ from these two groups changed in a span of 48 weeks. One of the tests they performed was the distance that a patient could walk in 6 minutes – a measurement known as the 6 min walk distance (6MWD). They found that this distance decreased in both groups at about the same rate. This is not surprising as both groups had KD and were essentially untreated groups.

They also measured something known as the ALSFRS-R. This is a self-assessment questionnaire (thus subjective) that attempts to measures how a patient feels they perform normal activities. The patient would be asked, for example, how are you doing at walking (or climbing stairs or swallowing). The patient then scores their answer on a 5 point scale, the higher the number, the better they felt they were doing. The researchers found that the ALSFRS-R scores fell for both groups, but it fell significantly more slowly for the PG than it did for the NTG. So essentially, the PG, who

thought they were receiving a drug that would lessen their symptoms, reported that they could function better than the NTG, the group that did not take any drug or treatment and had no preconceived expectations. This was despite the fact that both groups received nothing that would actually help them! Remember, there were no differences in an objective measurement (the 6MWD). Apparently, the idea that they

expected to be helped by a drug was enough to make them

feel that they were being helped.

Now this result is not groundbreaking research but I do think that it does have an important lesson for those of us with KD as well as those who are trying to cure KD. The results published by Sobue suggest that we need to be cautious when interpreting the results of a subjective test. The biases of the patients and the researchers can come into play in the form of a

placebo effect.

Sobue defined the placebo effect as “the improvement resulting from psycho physiological effects such as a positive expectation for a new treatment by patients and raters or a subconscious desire to meet the attending doctor’s expectations.” In other words, the patients feel like they are getting better because they

want to get better and not because they are getting better. It is common, I think, for people to underestimate the power of the placebo effect – it is real!

The Power of the Placebo Effect

The Power of the Placebo Effect

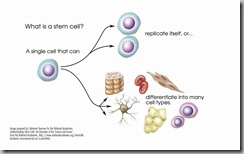

As patients who have a disease that has no treatments, we need to be aware of the power of the placebo effect when we hear of possible therapies, especially if they are not from a reliable source. Let me give an example. Until recently, a company in Germany (they were able to do this in Germany due to a legal loop hole, no other EU country, not the US or Canada would let them do what amounted to experimental surgery) advertised a safe and effective treatment for KD (as well as a host of many other neurological diseases) using stem cells.

At this time, this is no effective standard stem cell therapy for KD or the other diseases they claimed to cure. The website for this company referenced patient surveys to indicate efficacy of their treatment – I had not seen any reference to any objective data and they have not published any clinical trials. To no one’s surprise, they claim that something like 50% of the patients reported that they thought that the stem cells made them better.

Now if you think of these results in light of the Sobue paper, we have a group of individuals who desperately want to get better, so much that they spent tens of thousands of dollars to go to Germany and get this ‘treatment’. Just as in the PG group described above, this group felt like they were getting better when you asked them. But did they really get better? We cannot know for sure as there were no objective tests employed to verify that the disease progression had really been slowed.

Using patients from a similar clinic in China, a group of researchers did find that despite the reports from patients that they were better, objective criteria showed this was not the case. The stem cell treatment was not effective. This appears to be a classic case of the placebo effect. As an aside, the company in Germany has been closed by the German government after at least one patient died due to the stem cell treatment.

The ‘take home’ message from this is that we have to be alert and be able to differentiate viable treatments from scams and hearsay. Before embarking on any exotic treatment, look for objective evidence that it really works and always make such decisions in concert with your doctor.

Humility: A modest or low view of one's own importance; (or adjectival form: humble) is the quality of being modest, reverential, even politely submissive, and never being arrogant, contemptuous, rude or even self-abasing.

Humility: A modest or low view of one's own importance; (or adjectival form: humble) is the quality of being modest, reverential, even politely submissive, and never being arrogant, contemptuous, rude or even self-abasing.  The article concludes by Mr. Wood commenting on his relationship with golf. He said it if you want to know if a person is arrogant or humble; invite him to play a round of golf with you. Watch his reaction when he makes a bogey and when he makes a birdie. Does he ignore his success and talk about how he could improve his game or does he brag incessantly throughout the round? Golf will reveal his true character – and guarantee his humility.

The article concludes by Mr. Wood commenting on his relationship with golf. He said it if you want to know if a person is arrogant or humble; invite him to play a round of golf with you. Watch his reaction when he makes a bogey and when he makes a birdie. Does he ignore his success and talk about how he could improve his game or does he brag incessantly throughout the round? Golf will reveal his true character – and guarantee his humility.  Where I was once self-sufficient and confident, I often find myself in need of something or someone to just get through the day. Now that is humbling!

Where I was once self-sufficient and confident, I often find myself in need of something or someone to just get through the day. Now that is humbling!